Excerpt

Introduction: To Save Public Education We Must Reinvent It

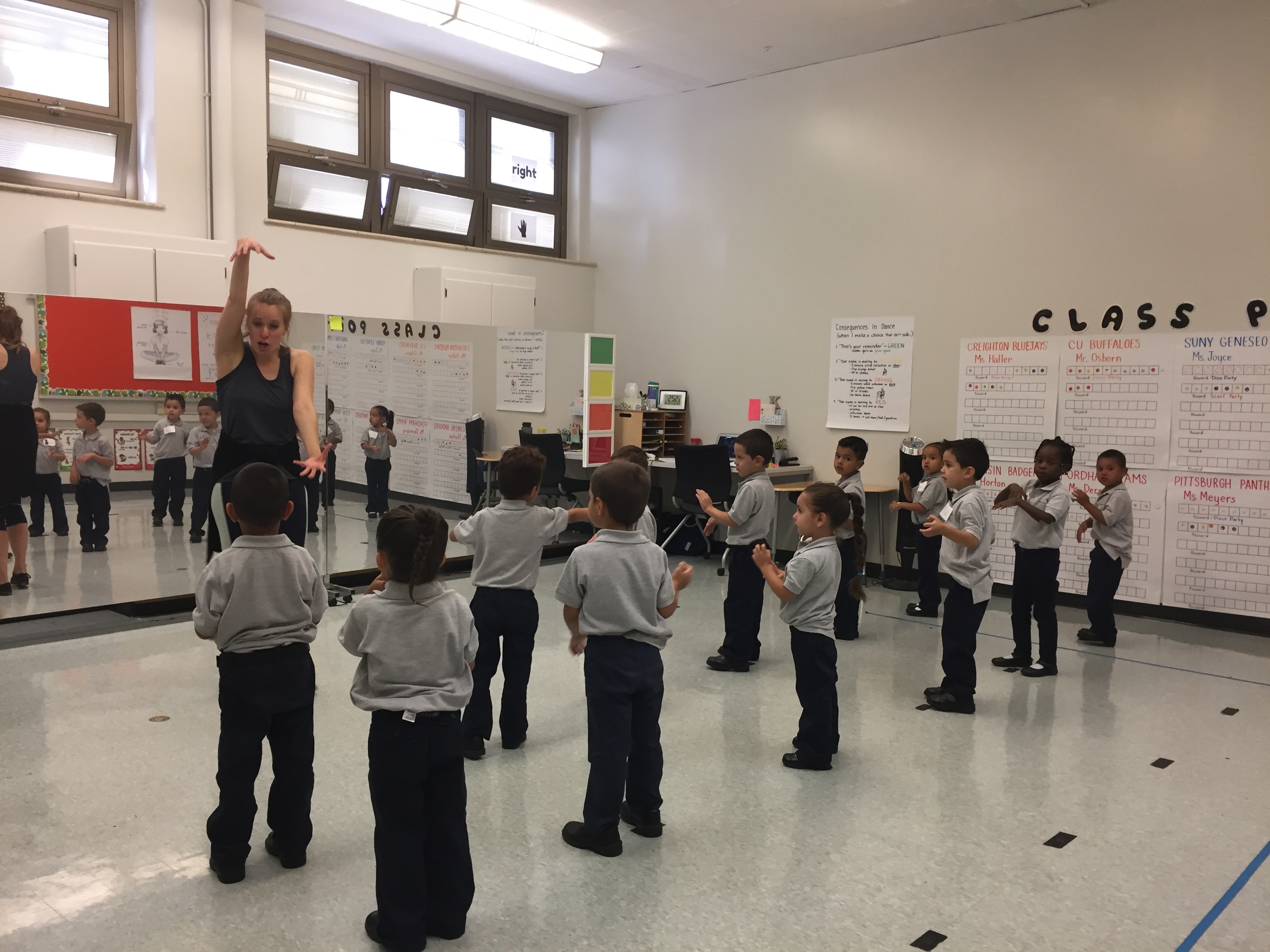

Students take dance class at Rocky Mountain Prep Southwest in Denver, Colo. (Photo credit: Romy Drucker)

If we were creating a public education system from scratch, would we organize it as most of our public systems are now organized? Would our classrooms look just as they did before the advent of personal computers and the Internet? Would we give teachers lifetime jobs after their second or third year of teaching? Would we let schools survive if, year after year, half their students dropped out? Would we send children to school for only eight and a half months a year and six hours a day? Would we assign them to schools by neighborhood, reinforcing racial and economic segregation?

Few people would answer yes to such questions. But in real life we don’t usually get to start over; instead, we have to change existing systems. And that threatens tightly held interests—such as teachers’ rights to lifetime jobs—triggering enormous political conflict.

One city did get a chance to start over, however. In 2005, after the third-deadliest hurricane in U.S. history, Louisiana’s leaders wiped the slate clean in New Orleans. After Katrina, they handed more than 100 of the city’s public schools—all but 17—to the state’s Recovery School District (RSD), created two years earlier to turn around failing schools. Over the next nine years, the RSD gradually turned them into charter schools—a new form of public school that has emerged over the last quarter century. Charters are public schools operated by independent, mostly nonprofit organizations, free of most state and district rules but held accountable for performance by written charters, which function like performance contracts. Most, but not all, are schools of choice. In 2017 the old Orleans Parish School Board, which is elected, decided to transition its last four traditional schools to charter status. Perhaps by next school year, 100 percent of the city’s public school students will attend charters.

The results should shake the very foundations of American education. Test scores, school performance scores, graduation and dropout rates, college-going rates, and independent studies all tell the same story: the city’s RSD schools have doubled or tripled their effectiveness. The district has improved faster than any other in the state—and no doubt in the nation. On several important metrics, New Orleans is the first big city with a majority of low-income minorities to outperform its state.

Washington, D.C., also started with a clean slate, but in a very different way. In 1996 Congress created the D.C. Public Charter School Board, which grants charters to nonprofit organizations to start schools. After 20 years of chartering, the board has performance contracts with about 65 nonprofit organizations to operate roughly 120 schools, and 46 percent of the city’s public school students attend them. Families choose the charter school they prefer. The board closes or replaces those in which kids are falling behind, while encouraging the best to expand or open new schools.

The competition from charters helped spur D.C.’s mayor to take control of the school district and initiate some of the most profound reforms any traditional district has embraced. Yet D.C.’s charter sector still has higher test scores, higher attendance, higher graduation and college enrollment rates, and more demand than the city’s traditional public schools. The difference is particularly dramatic with African American and low-income students, despite the fact that charters have received significantly less money each year—some $6,000 to $7,000 less per pupil—than district schools.

Leaders in other struggling urban districts have paid close attention to such reforms, and they are spreading. A decade ago the elected school board in Denver, frustrated by the traditional bureaucracy, decided to embrace charter schools. The board gave most charters space in district buildings and encouraged the successful ones to replicate as fast as possible. Then they began turning district schools into “innovation schools,” with many of the autonomies that help charters succeed. When these efforts began, Denver had the lowest academic growth of any of Colorado’s 20 largest cities. By 2012 it had the highest.

New Jersey followed New Orleans’s lead in Camden, where it took over the failing school district in 2013. Memphis and Indianapolis have embraced charters but also followed Denver’s lead with innovation schools. Massachusetts and the Springfield Public Schools have created an Empowerment Zone Partnership, with its own board, whose ten schools are treated much like charters. Three other states have copied Louisiana and created their own recovery districts. And 30 large districts belong to a network of “portfolio districts”—so called because they manage a portfolio of traditional and charter schools—which share what they have learned about what works and what doesn’t.

Most of the debate in this field is stuck on the tired issue of whether charter schools perform any better than traditional public schools. The evidence on that question, from dozens of careful studies, is clear: on average, charters outperform traditional public schools. The studies favored by charter critics come from Stanford University’s Center for Research on Educational Outcomes (CREDO). But even they show that, on average, students who spend four or more years in charter schools gain an additional two months of learning in reading and more than two months in math every year, compared to similar students in traditional public schools. Urban students gain five months in math and three and a half in reading. And charter parents are happier with their schools. On five key characteristics—teacher quality, school discipline, expectations for student achievement, safety, and development of character—13 percentage points more charter school parents were “very satisfied” with their schools than traditional school parents in 2016.

But when it comes to charter schools, “average” has little meaning, because the 43 states (and the District of Columbia) with charters all have different laws. Any good idea can be done poorly, and some states have proven it with their charter practices. One has to look beyond the averages to see the truth: In states where charter authorizers close or replace failing schools—a central feature of the charter model—charters vastly outperform traditional public schools, with students gaining as much as an extra year of learning every year. But in states where failing charters are allowed to remain open, they are, on average, no better than other public schools.

What matters is not whether we call them charter schools or district schools or “innovation schools” or “pilot schools,” but the rules that govern their operation. Do they have the autonomy they need to design a school model that works for the children they must educate? Are they free to hire the best teachers and fire the worst? Do they experience competition that drives them to continuously improve? Does the district give families a choice of different kinds of schools, designed to educate different kinds of learners? Do schools experience enough accountability—including the threat of closure if they fail—to create a sense of urgency among their employees? And when they close, are they replaced by better schools?

If the answer to these questions is yes, the system will be self-renewing: Its schools will constantly improve and evolve.

Leaders in cities as diverse as New Orleans, Washington, D.C, Denver, Indianapolis, and Camden have concluded that if they want more than incremental improvement, they have to embrace this new model. Their old systems were a century old, constructed for a different era. In their 21st century systems, the central administration steers but often contracts with others to operate schools. Some even develop arms-length, contractual relationships with some of their traditional schools, called “innovation” or “renaissance” or “pilot” schools.

The steering body, usually an elected school board and appointed superintendent but sometimes a mayor or appointed board and superintendent, awards charters (or other forms of performance agreements) to schools that meet emerging student needs. If the schools work, it expands them and replicates them. If they fail, it replaces them with better schools. Every year, it replaces the worst performers, replicates the best, and develops new models to meet new needs.

We have inherited 20th century systems whose centralized control and vast web of rules repel innovation and frustrate innovators. In their place, we are building 21st century systems that not only reward improvement but demand it. They leave behind the old model’s insistence on one organization, one best way to run a school, and one correct curriculum. In its place they create an ever-evolving network of schools designed for the Information Age, with multiple providers, different teaching methods, and choices for parents and their children.

Since both parents and teachers can choose among different kinds of schools, they are less likely to insist on the one best way—whether phonics or whole language, new math or old math. Elected school boards are politically free to create a more diverse set of schools, to meet the needs of an increasingly diverse body of students. The regimentation of pedagogy—which is profoundly unfair to children who don’t learn in the one best way—finally ends.

School boards in these 21st century systems also find it easier to create new kinds of schools when new needs and opportunities emerge. For example, traditional districts have been slow to create schools that use information technology in a meaningful way, because it requires a different configuration of personnel—something teachers and their unions find threatening. In the charter sector, however, schools have embraced technology, because school leaders feel an urgency to improve student achievement and are free to change their mix of personnel.

Equally important, a 21st century system gives school boards—elected or appointed—far more control over quality, because they can choose among competing operators, negotiate specific performance standards, and replace failing schools. Traditional districts do little of that.

More than any other single reform, this model breaks the political stranglehold interest groups have over elected school boards. Most school board members want to do what’s best for the children, but too often that creates problems for the adults in the system, who all vote. And when the children’s interests collide with the adults’, the children usually lose. This is why elected boards find it so hard to replace failing schools. Closing schools is political suicide, because employees, parents, and community members often protest, and the protesters all vote. Turnout in school board elections is often under 10 percent, so their votes usually carry the day. Hence board members who rock the boat know they are risking defeat.

In 21st century systems, where school boards contract with independent organizations to operate schools, the battle of self-interest is quite different. School operators still push for their own interests, but they no longer act as a unified block. For every school that opposes a particular change, another school supports it. Every time a school is closed for poor performance, other operators line up to take its place. Hence elected leaders are no longer so captive of adult interests; they have some freedom to do what is best for the children. And the principals and teachers feel enormous urgency to improve student learning—otherwise, their school might be replaced. For the first time, virtually every adult’s priority is student achievement.

The new formula—school autonomy, accountability for performance, diversity of school designs, parental choice, and competition between schools—is simply more effective than the centralized, bureaucratic approach we inherited from the 20th century. Separating steering from rowing makes all the difference. School boards and superintendents get to focus their energy on steering: on setting policy and direction and ensuring that schools deliver the results desired. Meanwhile, those doing the rowing—operating schools—have the freedom from bureaucratic constraints they need to maximize school performance.

This piece is excerpted from the introduction to Reinventing America’s Schools: Creating a 21st Century Education System, by David Osborne (Bloomsbury, Sept. 5, 2017).