Blog

Excerpt: How Washington, D.C. Is Reinventing Education

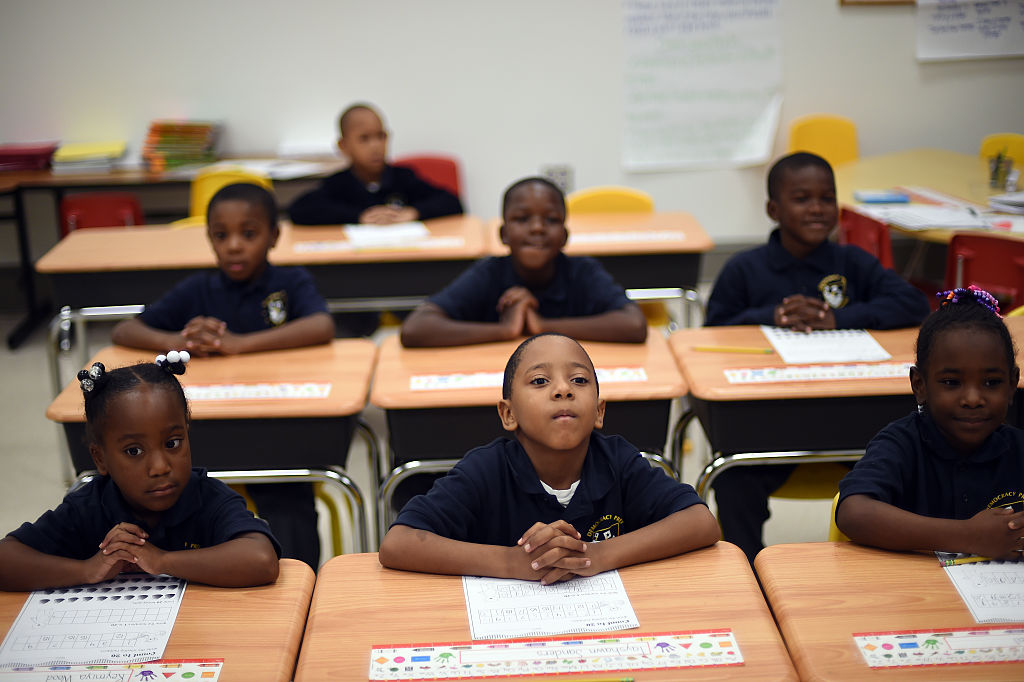

WASHINGTON, DC – September 24: With their arms orderly folded and rested on their desks, kindergarten students listen to their teacher at Democracy Prep Congress Heights in southeast of Washington, D.C., September 24, 2014. Democracy Prep is a charter school management company that’s taken over failing charter schools, acquiring all their assets, the building and all the students and started over. (Photo credit: The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Washington, D.C. offers a rare real-world laboratory: two public school systems of roughly equal size, occupying the same geography, with different governance models. The older of the two, D.C. Public Schools (DCPS), uses the unified governance model that emerged more than a century ago, in which the district operates all but one of its more than 110 schools and employs all their staff, with central control and most policies applied equally to most schools. Since 2007, when Michelle Rhee became chancellor, DCPS leaders have pursued the most aggressive, sustained reform effort of any unified urban district in America.

Competing with DCPS is a model designed and built largely in this 21st century. In 1996, Congress passed a bill creating the D.C. Public Charter School Board to authorize charters, while also giving DCPS the power to authorize them. The Charter Board owns or operates none of its schools; instead, it contracts with 65 independent organizations—all of them nonprofits—to operate more than 120 schools (as of 2016–17). Like DCPS, the Charter Board is a leader in its field, considered by experts one of the best charter authorizers in the nation.

After a contentious first decade, a remarkable amount of collaboration has emerged between these two sectors, as we will see. But ultimately, they are in direct competition. And the results of this competition have profound implications for the future of public education. If a traditional district led by the nation’s most aggressive reformers — a district making real progress — still cannot keep up with the charter sector, it suggests that the charter governance model is superior.

Congress passed legislation creating D.C.’s Public Charter School Board 18 months after the Republicans took control of both houses in the 1994 election. With D.C.’s local government facing a projected $700 million deficit, the Republicans put an appointed Control Board in place to run it, and that board commissioned a review of the school district.

The review labeled DCPS “educationally and managerially bankrupt.” The district was remarkably similar to New Orleans Public Schools: Half of all students dropped out, only 9 percent of ninth-graders in public high schools went on to graduate from college within five years, and almost two thirds of teachers reported that violent student behavior interfered with their teaching. “The longer students stay in the District’s public school system,” the report declared, “the less likely they are to succeed educationally.”

Board of Education members, who often used their positions as steppingstones to higher office, routinely engaged in patronage hiring. “Whenever a new superintendent was hired, it was understood that he or she would have to do political favors for board members whose political aspirations and path had been calculated far in advance,” says Kevin Chavous, who chaired the City Council’s Education Committee in the 1990s. Board members “got involved with every nitty-gritty detail,” steering contracts to supporters and jobs to friends and relatives.

A 1992 investigation had found a payroll full of “ghosts” — people drawing paychecks who had no responsibilities. Auditors were unable to track millions of dollars. Two of every three schools had faulty roofs, heating or air conditioning problems, and inadequate plumbing, according to the General Accounting Office. Nepotism was common, and Mayor Marion Barry steered contracts to supporters, even when it meant paying 25 percent more.

In 1996, the Financial Control Board stripped the elected school board of its authority over DCPS and handed the reins to an appointed board of trustees.

Meanwhile, House Speaker New Gingrich had asked moderate Republican Steve Gunderson, from Wisconsin, to come up with an education reform bill for D.C. Gingrich talked publicly about using D.C. as a “laboratory” for conservative reforms — particularly for a voucher program — which hardly endeared him to the city’s leaders. Gunderson’s young staff person, Ted Rebarber, had concluded that all public schools should be charter schools, or something like them. He wrote a memo for Gunderson advocating that approach. The congressman “was a little taken aback,” Rebarber says. “But to his credit, he was willing to look at it.”

The key turning point came when Gunderson and Rebarber met with Al Shanker, president of the American Federation of Teachers, with which the Washington Teachers Union was affiliated. Gunderson asked Shanker what he thought of charter schools, unaware that he was a key originator of the idea. “Shanker said, ‘Every school should be a charter school,’” Rebarber recalls. “Gunderson almost fell out of his chair, and he talked about it for days after the meeting. He told me, ‘Wow, we could really do something big, if that’s what Al Shanker thinks.’”

Rebarber had studied a dozen state charter bills that had already passed, and he picked out the best aspects of each one. He and Jim Ford, staff director for the City Council’s Education Committee, wrote a strong bill, which created two charter authorizers, the D.C. Board of Education and a new Public Charter School Board (PCSB). It allowed the city council to create a third — which it has never done — and required that D.C. spend the same amount per child in charters as in district schools.

After a long stalemate with Democrats over a voucher program Gingrich insisted on, the speaker finally dropped the voucher language and the bill passed with bipartisan support. It called for five-year charters, but charter leaders in other states were learning how hard it was to get long-term mortgage loans with only five-year guarantees of survival. So Congress passed an amendment extending charter terms to 15 years, with a serious review every five years.

The original law also lacked funding for buildings for charter schools. When local activists decided they needed to change that, they had only one Republican among their ranks: Malcolm “Mike” Peabody, who had been the civil rights officer for New York and Massachusetts state governments in the 1960s and whose brother Endicott Peabody had served as governor of Massachusetts. After a long stint at the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development, Mike Peabody had founded Friends of Choice in Urban Schools (FOCUS), in 1995, to push for a charter bill.

Peabody convinced Gingrich, who asked the House Appropriations subcommittee that dealt with D.C. to amend the bill to require facilities funding. Peabody then convinced City Councilman Kevin Chavous to base the funding formula for charter facilities on a rolling average of what DCPS had spent on facilities for the previous five years.