Blog

Excerpt: How Denver is Reinventing Education

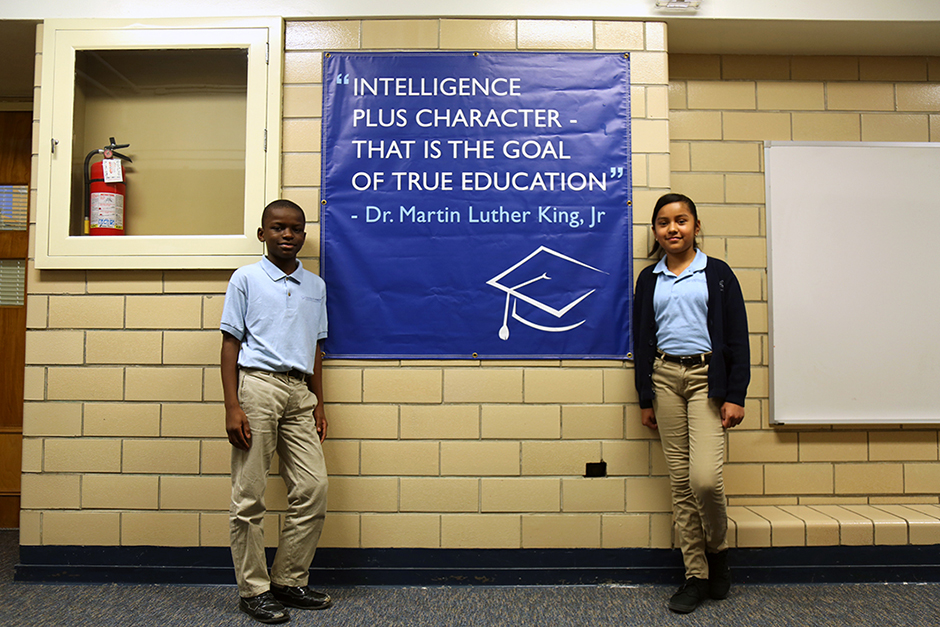

Emmanuel Beya and Abril Sierra, 5th graders in Cornell University classroom at University Prep–Steele Street. (Photo credit: Emmeline Zhao)

Many wonder whether a 21st century strategy is possible with an elected school board, because closing schools and laying off teachers triggers such fierce resistance. New Orleans and Washington, D.C., have been insulated from local electoral politics by Louisiana’s Recovery School District and D.C.’s Public Charter School Board, created by Congress. In other cities that are moving in this direction, such as Memphis, Tennessee, and Camden, New Jersey, recovery districts or state takeovers have driven the reforms.

All of which explains why reformers are paying close attention to Denver. With an elected board, Denver Public Schools (DPS) has embraced charter schools and created “innovation schools,” district schools with some of the autonomy charters enjoy. Between 2005 and 2015 it closed or replaced 48 schools and opened more than 70, the majority of them charters. In 2010 it signed a Collaboration Compact with charter schools, committing to equitable funding and a common enrollment system for charters and traditional schools, plus replication of the most effective schools, whether charter or traditional.

Of DPS’s 204 schools in 2016–17, 56 were charters, which educated 21 percent of its students, and 47 were innovation schools, which educated 20.5 percent. In 2015 the Board of Education voted for a major expansion of successful charter schools. And in 2016 it created an innovation zone, called the Luminary Learning Network, with an independent, nonprofit board that has a three-year memorandum of understanding with the district. Beginning with four innovation schools but able to expand, the zone could help DPS give innovation schools the true autonomy they need to excel.

For years, Denver’s reforms stirred controversy. When the Board of Education closed or replaced failing schools, protests erupted and board meetings dragged into the wee hours. During four of Tom Boasberg’s first five years as superintendent, he had only a four-three majority on the board. But the strategy produced steady results: In 2005, Denver had the lowest rates of academic growth among Colorado’s ten largest districts; since 2012 it has ranked at the top.

Denver still has a long way to go, but its progress offers hope to other urban districts with elected school boards, which remains the norm. A combination of courageous leadership, political skill, and positive results has yielded broad support for its strategy of closing failing schools and replacing them with charters and innovation schools. Voters have responded by electing a 7–0 majority in support of this strategy.

***

Tom Boasberg and the school board deserve credit for putting in place many of the elements of a 21st century strategy. They have embraced charters, committing to expand their numbers even though they have no more empty buildings. They have finally agreed to be as tough in closing failing district schools as they are with failing charters, and to treat both sectors equally in awarding buildings. (The board voted to replace two traditional schools and close a third in November 2016, and there was no public fuss.) They have created an innovation zone that may finally give district schools the autonomy they need. They are moving more special education centers for extremely disabled students into charters, correcting an imbalance. And they have created an “innovation lab” for school design, called the Imaginarium. It runs design challenges in which people compete to develop the most innovative school designs, with facilitated sessions to help them and a prize of $100,000 for the best design. It has worked with up to 20 schools at a time.

Meanwhile Denver has accomplished a dramatic expansion of full-day preschool, which is now available for most four-year-olds and a few high-risk and special-needs three-year-olds. Voters have funded the Denver Preschool Program with a sales tax increase for the last decade, and the state and district also provide money. Test scores and evaluations suggest the investment is paying off.

Yet DPS still has a long way to go before most students graduate and most graduates are ready for college or a career. By 2016, only about a third of students met or exceeded Common Core Standards. Achievement gaps by race and income were wide and growing wider.

“I don’t think we have figured out how to educate low-income kids,” says board member Barbara O’Brien, a former state legislator and lieutenant governor who has been at the forefront of education reform for decades. “There are fabulous, charismatic leaders, a Bill Kurtz, a Chris Gibbons [founder and CEO of Strive Prep]—they’re out there. But in terms of a whole district of 90,000 students, the change is incremental. We’re not moving the needle for the whole district.”

In contrast, Denver’s charter schools have figured out how to educate low-income children. Hence the first two challenges Denver faces, if it wants to accelerate its progress, are to close more failing schools and open more charters.